Translate

domingo, 28 de febrero de 2016

Gravitación : Manuel Vicent

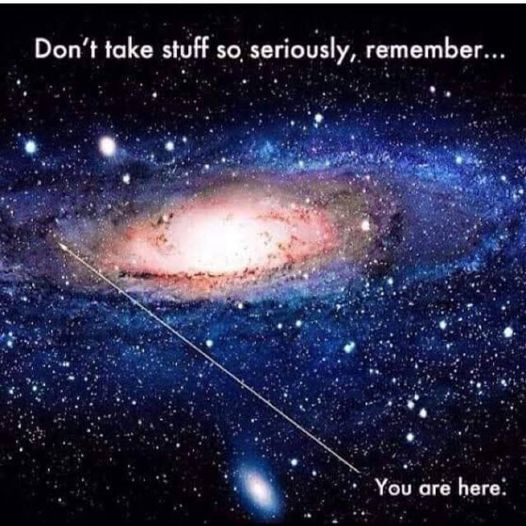

Antes de que Einstein en 1916 demostrara teóricamente la existencia de las ondas gravitacionales, producto del choque de dos agujeros negros que tuvo su origen a miles de millones de años luz, y la ciencia fuera capaz de detectarlas, algunos seres privilegiados de nuestro planeta ya las habían incorporado a su espíritu. La infinita armonía de ese sonido del espacio puede que estuviera inserta en los golpes de cincel de Fidias, en el ritmo de un verso de Ovidio, en la Venus de Botticelli saliendo del mar, en la inspiración de Mozart al componer su concierto de clarinete, en la garganta de Louis Armstrong. El alucinante cataclismo que produjeron en un punto del universo dos galaxias al devorarse, después de miles de millones de años luz, tal vez ha terminado vibrando en las cuerdas del arpa con que una chica angelical ameniza una cena de mafiosos en un restaurante con tres estrellas Michelin caídas también del espacio. De la misma forma que las ondas gravitacionales han sido captadas por el experimento LIGO, puede que algún día la física cuántica demuestre que el alma de las personas y de los animales también obedece a la fórmula E=mc2 de Einstein como resultado de aquella explosión. ¿Qué es el espíritu sino una contracción del tiempo y el espacio? Las almas que pueblan esta mota de polvo cósmico que es la Tierra forman un solo cuerpo místico, cuya materia al transformarse en energía engendra el bien y el mal, el paraíso y el infierno, la inteligencia clara y el fanatismo. De aquella inmensa bola de fuego se ha derivado la sabiduría de Platón, la serenidad de Buda, la lámpara de Aladino, el éxtasis de los sufíes, el sudor de todos los esclavos, la hoguera en la que ardió Giordano Bruno, la navaja de Jack the Ripper, los pies alados de Margot Fonteyn. Todos estamos sin saberlo en un agujero negro

sábado, 20 de febrero de 2016

Entrevista a Kapuscinski en Negro sobre Blanco

Entrevista de Fernando Sánchez Dragó a Ryszard Kapuściński con motivo de la entrega el premio Príncipe de Asturias de la Comunicación otorgado al periodista, historiador y ensayista polaco en 2003. Kapuściński habla en español, cuenta que lo aprendió en América Latina cuando fue corresponsal durante finales de los 60. Habla de algunas anécdotas y sucesos plasmados en sus libros, del periodismo y la literatura, de cómo contar la realidad. Recuerda sus memorias de infancia, de la segunda guerra mundial, y cómo se siente identificado con la gente pobre y sin recursos que ha conocido a lo largo de su vida. Considera que viajar y escuchar las voces de la gente es la mejor manera de contar y plasmar la historia, de se un verdadero reportero. En su vida de corresponsal le han sucedido muchísimas cosas, ha vivido situaciones de riesgo mortal, y ha visto y relatado en primera persona distintas guerras, golpes de Estado, y revoluciones tanto en Asia y Europa como en Américas Latina y África.

viernes, 19 de febrero de 2016

Murió Umberto Eco

En un discurso en la Universidad de Turín, Eco aplicó su mirada crítica –no todo es positivo ni negativo en su totalidad—a las redes sociales: “El fenómeno de Twitter es por una parte positivo, pensemos en China o en Erdogan. Hay quien llega a sostener que Auschwitz no habría sido posible con Internet, porque la noticia se habría difundido viralmente. Pero por otra parte da derecho de palabra a legiones de imbéciles”.

Hugo Marietan: “Donde hay poder, hay psicópatas”

Hugo Marietan

“La política es un ámbito donde el psicópata se mueve como pez en el agua, lo que no significa que todos los líderes o políticos sean psicópatas. Pero sí que allí donde hay poder, hay psicópatas, que no distinguen ideologías. Por eso los encontramos en la izquierda y en la derecha”, define el doctor Hugo Marietan, médico psiquiatra y uno de los principales especialistas argentinos en psicopatía. Docente universitario y autor de varios libros sobre su especialidad, Marietan es referencia obligada para aquellos que les ponen la lupa a estas personalidades atípicas, que no necesariamente son las que protagonizan hechos policiales de alto impacto. Para decirlo de algún modo, cuando hablamos de psicópata no necesariamente nos referimos a un criminal al estilo de Hannibal Lecter, el perturbado psiquiatra de El silencio de los inocentes, sino a aquellas personalidades que la psicología bautizó como “psicópatas cotidianos”.

Tal vez el aporte más novedoso de este profesional, miembro de la Asociación Argentina de Psiquiatría, considerado una autoridad en su especialidad, es que el psicópata no es un enfermo mental sino una manera de ser en el mundo. Es decir: una variante poco frecuente del ser humano que se caracteriza por tener necesidades especiales. El afán desmedido de poder, de protagonismo o matar pueden ser algunas de ellas. Funcionan con códigos propios, distintos de los que maneja la sociedad. También tienen una lógica propia y suelen estar dotados para ser capitanes de tormenta por su alto grado de insensibilidad y tolerancia a situaciones de extrema tensión.

Marietan es autor de Sol negro: un psicópata en la familia y El jefe psicópata, entre otros libros.

–¿Cómo distinguimos fácilmente a un político psicópata? ¿Qué características tiene?

–Trabaja siempre para sí mismo, aunque diga lo contrario, pero tapa esa ambición con objetivos supranacionales: la seguridad, la patria, la pobreza, la revolución, etcétera. Es un mentiroso e incluso puede fingir sensibilidad. Actúa. Y uno le cree una y otra vez porque es muy convincente. Un dirigente común sabe que tiene que cumplir su función durante un tiempo determinado. Y, cumplida su misión, se va. Al psicópata, en cambio, una vez que está arriba, no lo saca nadie: quiere estar una vez, dos veces, tres veces. No larga el poder, y mucho menos lo delega. Otra característica es la manipulación que hace de la gente. Alrededor del dirigente psicópata se mueven obsecuentes, gente que, bajo su efecto persuasivo, es capaz de hacer cosas que de otro modo no haría. Y puede ser gente muy inteligente.

–¿Y por qué gente inteligente sería obsecuente de un psicópata?

–Claro, es lo que uno se pregunta: “¿Cómo Fulano o Mengano se arrastra ante esta persona?”. Bueno, primero porque es vulnerable a los psicópatas. El psicópata trabaja siempre con la mente del otro, y cuando te relacionás con él, y sos vulnerable, se mete en tu cerebro. Te captura. Y cuando eso sucede, el obsecuente se convierte en un esclavo mental. Te come la cabeza, como dicen los chicos, y es muy difícil salir de ese circuito. El psicópata es además un manipulador; manda a hacer, nunca hace él. Es ingrato, carece de sensibilidad, de empatía, de poder ponerse en el lugar del otro. Y cuando lucha por el poder, aísla a su enemigo y ningunea. O mejor dicho, manda a los demás a ningunear al enemigo. Y algo importante: el psicópata tiene una lógica, un modo de pensar muy distinto a la media de la sociedad. Una lógica que le va transmitiendo a los obsecuentes que tiene danzando a su alrededor.

–¿No tiene cura?

–No. Pero sabe muy bien qué está bien y qué está mal, por eso decimos que no hay “tipos” entre los psicópatas sino grados o intensidades diversas. Así, el violador serial sería un psicópata más intenso o extremo que el cotidiano, pero portador de la misma personalidad. No reconoce errores propios, por eso no puede corregir el rumbo.

–¿Y no hay forma de ejercer el poder sin ser un psicópata? Porque digamos que en algún punto todos los políticos trabajan para sí mismos.

–Antes de responder, una aclaración importante. Por supuesto que se puede ejercer el poder sin ser psicópata y, de hecho, la enorme mayoría de los líderes no lo son. En un punto, es cierto que todos los políticos, de algún modo, trabajan para sí mismos porque quieren ser reelectos, pero también trabajan para los demás, buscan generar beneficios. Al psicópata, en cambio, eso no le importa en absoluto y si beneficia a alguien es por algún efecto colateral. El líder comunitario se distingue también porque forma alianzas y consensúa. Cede para avanzar en la carrera política. El psicópata carece de capacidad para el consenso porque, justamente, no puede ponerse en el lugar de otra persona. Por eso, es difícil entrar en su cabeza. Un político normal no lo comprende: “Si yo estuviera en su lugar, cedería o consensuaría, incluso para conservar el poder”, piensa el líder no psicópata. Pero el psicópata no piensa así.

–¿Y están en la izquierda y en la derecha?

–Y entre los moderados también, que necesitan ser conducidos. Allí donde hay poder, hay psicópatas. El psicópata establece relaciones piramidales. Una de sus frases puede ser: “Están conmigo o en contra de mí”.

–¿Cuál es el efecto que se genera alrededor de un líder psicópata?

–La tensión. Siempre son generadores de tensión y de conflicto, de división. En un consorcio, los que terminan peleados son los demás, él siempre cae parado aunque haya generado el conflicto. En una familia, los que se enferman son los demás, generalmente por el estrés generado, mientras él sigue fresquito como una lechuga.

–¿Hay sociedades más propensas que otras a depositar el liderazgo en dirigentes psicopáticos?

–Sí, claro, las que tienen tendencia a generar crisis recurrentes, porque el psicópata es un ser que brilla y es buscado en las situaciones de máxima tensión. El psicópata florece en las crisis porque es frío, calculador y tiene un saber hacer en situaciones de tensión que la persona común no.

–¿Y cómo se reemplaza a un líder psicopático?

–Con otro psicópata o con la unión de varios políticos comunes, con una alianza. Para un líder normal solo, resulta imposible.

–¿Qué le diría a un extranjero que pregunta por Argentina ?

–Tres cosas. Primero, lo interesante que son los problemas que tenemos. Segundo, lo insólito que son las soluciones que se nos ocurren. Y tercero, lo poco que aprendemos de nuestros errores.

miércoles, 17 de febrero de 2016

Lao Tzu , tres cosas a enseñar

I have just three things to teach: #simplicity, #patience, #compassion. These three are your greatest treasures." -Lao Tzu

lunes, 15 de febrero de 2016

Que significa ejercer un oficio de lo humano

Perrenoud, un pedagogo francés, escribe (hablando de la profesión de la enseñanza):

“Ejercer serenamente un oficio de lo humano significa saber con cierta precisión, por lo menos a posteriori, lo que depende de la acción profesional y lo que escapa de ella. No se trata de cargar con todo el peso del mundo, responsabilizándose de todo, sintiéndose continuamente culpable; es, al mismo tiempo, no ponerse una venda en los ojos, percibir lo que podríamos haber hecho si hubiéramos comprendido mejor lo que ocurría, si nos hubiéramos mostrado más rápidos, más perspicaces, más tenaces o más convincentes… Para verlo más claro, a veces se debe aceptar el reconocimiento de que podríamos haberlo hecho mejor y comprender por qué no lo hemos conseguido. El análisis no suspende el juicio moral, no vacuna contra la culpabilidad, sino que induce al practicante a aceptar que no es una máquina infalible, a tener en cuenta sus preferencias, dudas, espacio vacíos, lapsos de memoria, opiniones adoptadas, aversiones y predilecciones, y otras debilidades inherentes a la condición humana”

Principio de Peter

El principio de Peter o principio de incompetencia de Peter,[1] está basado en el «estudio de las jerarquías en las organizaciones modernas», o lo que Laurence J. Peter denomina «hierachiology» («jerarquiología»).[2] Afirma que las personas que realizan bien su trabajo son promocionadas a puestos de mayor responsabilidad, a tal punto que llegan a un puesto en el que no pueden formular ni siquiera los objetivos de un trabajo, y alcanzan su máximo nivel de incompetencia. Este principio, formulado por el catedrático de ciencias de la educación de la Universidad del Sur de California en su libro The Peter Principle, de 1969,[2] afirma que:

Como corolario de su famoso principio, Laurence J. Peter deduce los dos siguientes:

En una jerarquía, todo empleado tiende a ascender hasta su nivel de incompetencia: la nata sube hasta cortarse.Según algunas fuentes[¿cuál?], el primero en hacer referencia a este concepto fue José Ortega y Gasset quien en la década de 1910 dio forma al siguiente aforismo: "Todos los empleados públicos deberían descender a su grado inmediato inferior, porque han sido ascendidos hasta volverse incompetentes".[3]

Laurence J. Peter

Como corolario de su famoso principio, Laurence J. Peter deduce los dos siguientes:

- Con el tiempo, todo puesto tiende a ser ocupado por un empleado que es incompetente para desempeñar sus obligaciones.

- El trabajo es realizado por aquellos empleados que no han alcanzado todavía su nivel de incompetencia.

domingo, 14 de febrero de 2016

sábado, 13 de febrero de 2016

Burman

El cineasta reniega de nostalgias: “Ese retorno es como si te quedas atascado en el nivel siete de un videojuego y debes retornar varias pantallas atrás para coger una herramienta con la que pasar al nivel ocho. No sabes lo que buscas hasta que lo encuentras”.

Burman sintió que había abandonado sus temas, “la ligazón con la infancia y la paternidad”, el día en que descubrió que para rodar un dedo había a su alrededor 10 camiones con material fílmico. “No digo que fuera malo, pero me arrastraba el proceso industrial. Perdí la pulsión de contar algo con urgencia. Con El rey del Once vuelvo a filmar una película con las manos, porque cojo la cámara, y con los pies, porque todas las localizaciones están en un radio de 500 metros”.

Como padre de tres hijos, Burman reconoce que se pasa todo el día viajando. “Creo más en la transmisión de valores que en esa moda actual de paternidad presente. Colocas balizas en la vida de un hijo para que le sirvan de guía. Y si estás a su lado, pues mejor. En cualquier caso la paternidad es una ficción que trabajas día a día para que los hijos te reconozcan. Con las madres está la ligazón carnal, salen de su cuerpo. Pero nosotros… Sinceramente, ¿tú has visto alguna película, y olvídate de los culebrones, en la que de repente aparezca una mujer y diga: ‘Yo soy tu madre”.

Burman sintió que había abandonado sus temas, “la ligazón con la infancia y la paternidad”, el día en que descubrió que para rodar un dedo había a su alrededor 10 camiones con material fílmico. “No digo que fuera malo, pero me arrastraba el proceso industrial. Perdí la pulsión de contar algo con urgencia. Con El rey del Once vuelvo a filmar una película con las manos, porque cojo la cámara, y con los pies, porque todas las localizaciones están en un radio de 500 metros”.

Como padre de tres hijos, Burman reconoce que se pasa todo el día viajando. “Creo más en la transmisión de valores que en esa moda actual de paternidad presente. Colocas balizas en la vida de un hijo para que le sirvan de guía. Y si estás a su lado, pues mejor. En cualquier caso la paternidad es una ficción que trabajas día a día para que los hijos te reconozcan. Con las madres está la ligazón carnal, salen de su cuerpo. Pero nosotros… Sinceramente, ¿tú has visto alguna película, y olvídate de los culebrones, en la que de repente aparezca una mujer y diga: ‘Yo soy tu madre”.

Muerte feliz - Jose Arregui

Estos días he releído el último

libro de H. Küng, aún no traducido al español, un texto breve del año 2014 con

el que a sus 86 años, aquejado por un Párkinson progresivo, quiso coronar su

vida y toda su obra. El título constituye más que un mero testamento vital, es

un programa de vida: “Muerte feliz”.

¿Contradicción?

Más bien, paradoja de la vida, que solo puede ser feliz dándose. Paradoja de la

muerte que se hace donación y se vuelve decisión, expresión, culminación de la

vida. La muerte puede ser feliz, pues la vida que se da no muere. ¿Te parece un

juego de palabras vacío? Para H. Küng es el horizonte que ilumina su vida

entera incluida la muerte. Sabe de lo que habla, pues a ello ha consagrado sus

inagotables energías físicas, emocionales, intelectuales, espirituales.

Muerte feliz: eso significa

“eutanasia” en su origen y etimología, aunque los nazis degradaron su sentido

al utilizarlo para designar sus prácticas de exterminio, de muerte infeliz.

Muerte feliz o eutanasia significa morir sin tristeza y sin dolor, o con el

mínimo de tristeza y de dolor inevitable. Morir en plena conciencia. Despedirse

serenamente de los seres queridos. Asumir sin angustia la pena de la

separación; en la pena hay consuelo, en la angustia no; la pena no impide la

felicidad, la angustia sí.

Morir

en profundo asentimiento a toda la vida, aceptándolo todo, diciendo sí a todo,

también a las heridas sufridas y, lo que es mucho más difícil, a las heridas

infligidas: no he sido perfecto, lo siento, pero a esto he llegado, y así está

bien; me gustaría que muchas cosas hubieran sido mejores, pero está bien como

está; digo sí a todo, sin justificar nada. Decir: “Mi obra está acabada: ahí os

la dejo”. Y no hace falta que sea una “gran obra”, como la de Hans Küng, ni nadie

puede medir la grandeza de la obra por el tamaño o el número o la calidad de

los libros escritos, ni por el éxito logrado, o el influjo ejercido. Coronar la

vida humildemente. Morir en paz.

Pues

bien, como creyente pensador y humanista, afirma Küng: en el momento en que mi

vida ya no posee para mí calidad humana suficiente, puedo y debo elegir esa

“muerte feliz”, digna, bella, buena. Muerte hermana, no enemiga. Hay un tiempo

para vivir y un tiempo para morir. Y yo puedo, debo decidirlo responsablemente.

“El ser humano tiene el derecho a morir cuando no tiene ninguna esperanza de

seguir llevando lo que según su entender es una existencia humana”. Rehusar

prolongar indefinidamente la vida temporal forma parte del arte de vivir y de

la fe en la vida eterna. Ya se había pronunciado en el mismo sentido hace 20

años, en 1995, en otro libro (Morir dignamente,

Trotta 1997) escrito en colaboración con su amigo y colega Walter Jens.

Asistimos

a un cambio radical de paradigma. La legislación social de los diversos países

–con contadas excepciones como Holanda o Suiza– adolece todavía de un gran

retraso respecto de la opinión social. Y el retraso es más grande en el caso de

la jerarquía eclesial. Sostener, como sostiene, que solo es lícita la “ayuda

pasiva” (desconectar un aparato de alimentación o de respiración, por ejemplo)

no deja de ser una ficción. ¿Hay tanta diferencia entre desconectar un aparato

y proporcionar una dosis mayor de morfina que me llevará a la muerte o al

descanso final? La jerarquía eclesiástica corre el riesgo de volver a

equivocarse, como se equivocó a propósito de los métodos de contracepción o de

fecundación llamados “artificiales”.

Elegir

la muerte de manera humana es la forma final de elegir la vida de manera humana.

Y la humanidad no está definida ni dictada por una divinidad exterior ni

representada por ninguna religión. El creyente debiera una muerte feliz como definitiva

donación confiada de sí a la Realidad primera y última, como tránsito a la

Realidad profunda, a la Realidad Fontal, a la Vida sin origen ni fin. Decir que

no podemos elegir la muerte porque no somos dueños de la vida es una máxima

tramposa. No somos dueños de la vida ni de la muerte, pero somos responsables

de la vida y, por lo tanto, también de la muerte, y aquí no es decisiva la

distinción entre creyente e increyente. No solo podemos, sino que debemos

elegir responsablemente –digo responsablemente– cuándo y cómo morir, sin otro

límite que nuestro bienestar y el bienestar común, empezando por el de las personas

más allegadas. Y los médicos y las personas más próximas debieran poder atender

la demanda de quien libremente les pide –o de quien libremente hubiera dejado

expresada esa demanda– una ayuda para bien morir.

Es

una exigencia del cuidado de la vida, y no hay otro mandato divino ni otra

divinidad que la Vida, el Cuidado, la Bondad y el Buen Vivir.

(Publicado en DEIA y los Diarios del Grupo

Noticias el 7 de febrero de 2016)

viernes, 12 de febrero de 2016

lunes, 8 de febrero de 2016

domingo, 7 de febrero de 2016

sábado, 6 de febrero de 2016

viernes, 5 de febrero de 2016

Aldous Huxley on how we becomme who we are .....

Aldous Huxley on How We Become Who We Are, How to Get Out of Our Own Way, and the Necessity of Mind-Body Education

“In all the activities of life, from the simplest physical activities to the highest intellectual and spiritual activities, our whole effort must be to get out of our own light.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

Aldous Huxley endures as one of the most visionary and unusual minds of the twentieth century — a man of strong convictions about drugs, democracy, and religion and immensely prescient ideas about the role of technology in human life; a prominent fixture ofCarl Sagan’s reading list; and the author of a little-known allegorical children’s book.

Aldous Huxley endures as one of the most visionary and unusual minds of the twentieth century — a man of strong convictions about drugs, democracy, and religion and immensely prescient ideas about the role of technology in human life; a prominent fixture ofCarl Sagan’s reading list; and the author of a little-known allegorical children’s book.

In one of his twenty-six altogether excellent essays inThe Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment(public library), Huxley sets out to answer the question of who we are — an enormous question that, he points out, entails a number of complex relationships: between and among humans, between humanity and nature, between the cultural traditions of different societies, between the values and belief systems of the present and the past.

Writing in 1955, more than two decades after the publication of Brave New World, Huxley considers the stakes in this ultimate act of bravery:

What are we in relation to our own minds and bodies — or, seeing that there is not a single word, let us use it in a hyphenated form — our own mind-bodies? What are we in relation to this total organism in which we live?[…]The moment we begin thinking about it in any detail, we find ourselves confronted by all kinds of extremely difficult, unanswered, and maybe unanswerable questions.

These unanswerable questions, the value of which the great Hannah Arendt wouldextol as the basis of our civilization two decades later, challenge the very “who” of who we are. Huxley illustrates this with a most basic example:

I wish to raise my hand. Well, I raise it. But who raises it? Who is the “I” who raises my hand? Certainly it is not exclusively the “I” who is standing here talking, the “I” who signs the checks and has a history behind him, because I do not have the faintest idea how my hand was raised. All I know is that I expressed a wish for my hand to be raised, whereupon something within myself set to work, pulled the switches of a most elaborate nervous system, and made thirty or forty muscles — some of which contract and some of which relax at the same instant — function in perfect harmony so as to produce this extremely simple gesture. And of course, when we ask ourselves, how does my heart beat? how do we breathe? how do I digest my food? — we do not have the faintest idea.[…]We as personalities — as what we like to think of ourselves as being — are in fact only a very small part of an immense manifestation of activity, physical and mental, of which we are simply not aware. We have some control over this inasmuch as some actions being voluntary we can say, I want this to happen, and somebody else does the work for us. But meanwhile, many actions go on without our having the slightest consciousness of them, and … these vegetative actions can be grossly interfered with by our undesirable thoughts, our fears, our greeds, our angers, and so on…The question then arises, How are we related to this? Why is it that we think of ourselves as only this minute part of a totality far larger than we are — a totality which according to many philosophers may actually be coextensive with the total activity of the universe?

At a time when Alan Watts was beginning to popularize Eastern teachings in the West and prominent public figures like Jack Kerouac were turning to Buddhism, Huxley advances this cross-pollination of East and West. With an eye to pioneering psychologist and philosopher William James, who was among his greatest influences, he considers the notion that our consciousness is the filtering down of a larger universal consciousness, distilled in a way that benefits our survival:

Obviously, if we have to get out of the way of the traffic on Hollywood Boulevard, it is no good being aware of everything that is going on in the universe; we have to be aware of the approaching bus. And this is what the brain does for us: It narrows the field down so that we can go through life without getting into serious trouble.But … we can and ought to open ourselves up and become what in fact we have always been from the beginning, that is to say … much more widely knowing than we normally think we are. We should realize our identity with what James called the cosmic consciousness and what in the East is called the Atman-Brahman. The end of life in all great religious traditions is the realization that the finite manifests the Infinite in its totality. This is, of course, a complete paradox when it is stated in words; nevertheless, it is one of the facts of experience.

But this deeper and more expansive sense of self, Huxley argues, is habitually obscured by the superficial shells we mistake for our selves:

The superficial self — the self which we call ourselves, which answers to our names and which goes about its business — has a terrible habit of imagining itself to be absolute in some sense… We know in an obscure and profound way that in the depths of our being … we are identical with the divine Ground. And we wish to realize this identity. But unfortunately, owing to the ignorance in which we live — partly a cultural product, partly a biological and voluntary product — we tend to look at ourselves, at this wretched little self, as being absolute. We either worship ourselves as such, or we project some magnified image of the self in an ideal or goal which falls short of the highest ideal or goal, and proceed to worship that.

Huxley admonishes against “the appalling dangers of idolatry” — a misguided attempt at communion with a greater truth that, in fact, renders us all the more separate:

Idolatry is … the worship of a part — especially the self or projection of the self — as though it were the absolute totality. And as soon as this happens, general disaster occurs.

Nearly half a century before Adrienne Rich lamented “the corruptions of language employed to manage our perceptions” in her spectacular critique of capitalism, Huxley argues that the uses and misuses of language mediate our relationship with the self and are responsible for our tendency to confuse the deeper self with the superficial self:

This is the greatest gift which man has ever received or given himself, the gift of language. But we have to remember that although language is absolutely essential to us, it can also be absolutely fatal because we use it wrongly. If we analyze our processes of living, we find that, I imagine, at least 50 percent of our life is spent in the universe of language. We are like icebergs, floating in a sea of immediate experience but projecting into the air of language. Icebergs are about four-fifths under water and one-fifth above. But, I would say, we are considerably more than that above. I should say, we are the best part of 50 percent — and, I suspect, some people are about 80 percent above in the world of language. They virtually never have a direct experience; they live entirely in terms of concepts.

It’s a sentiment triply poignant today, in an era when the so-called social media rely on language — both textual and the even more commodified visual language of photography — to convey and to manicure our conceptual perception of each other, often at the expense of the deeper truth of who we are. To be sure, Huxley recognizes that this reliance on concepts is evolutionarily necessary — another sensemaking mechanism for narrowing and organizing the uncontainable chaos of reality into comprehensible bits:

When we see a rose, we immediately say, rose. We do not say, I see a roundish mass of delicately shaded reds and pinks. We immediately pass from the actual experience to the concept.[…]We cannot help living to a very large extent in terms of concepts. We have to do so, because immediate experience is so chaotic and so immensely rich that in mere self-preservation we have to use the machinery of language to sort out what is of utility for us, what in any given context is of importance, and at the same time to try to understand—because it is only in terms of language that we can understand what is happening. We make generalizations and we go into higher and higher degrees of abstraction, which permit us to comprehend what we are up to, which we certainly would not if we did not have language. And in this way language is an immense boon, which we could not possibly do without.But language has its limitations and its traps.

Much like Simone Weil argued that the language of algebra hijacked the scientific understanding of reality in the early twentieth century, Huxley asserts that verbal language is leading us to mistake the names we give to various aspects of reality for reality itself:

In general, we think that the pointing finger — the word — is the thing we point at… In reality, words are simply the signs of things. But many people treat things as though they were the signs and illustrations of words. When they see a thing, they immediately think of it as just being an illustration of a verbal category, which is absolutely fatal because this is not the case. And yet we cannot do without words. The whole of life is, after all, a process of walking on a tightrope. If you do not fall one way you fall the other, and each is equally bad. We cannot do without language, and yet if we take language too seriously we are in an extremely bad way. We somehow have to keep going on this knife-edge (every action of life is a knife-edge), being aware of the dangers and doing our best to keep out of them.

This, perhaps, is why David Whyte — as both a poet and a philosopher — is so well poised to unravel the deeper, truer meanings of common words.

The root of our over-reliance on language, Huxley argues, lies in our flawed education system, which is predominantly verbal at the expense of experiential learning. (A similar lament led young Susan Sontag to radically remix the timeline of education.) In a prescient case for today’s rise of tinkering schools and mind-body training for kids, Huxley writes:

The liberal arts … are little better than they were in the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages the liberal arts were entirely verbal. The only two which were not verbal were astronomy and music… Although for hundreds of years we have been talking about mens sana in corpore sano, we really have not paid any serious attention to the problem of training the mind-body, the instrument which has to do with the learning, which has to do with the living. We give children compulsory games, a little drill, and so on, but this really does not amount in any sense to a training of the mind-body. We pour this verbal stuff into them without in any way preparing the organism for life or for understanding its position in the world — who it is, where it stands, how it is related to the universe. This is one of the oddest things.Moreover, we do not even prepare the child to have any proper relation with its own mind-body.

Long before Buckminster Fuller admonished against the evils of excessive specialization and Leo Buscaglia penned his magnificent critique of the education system’s industrialized conformity, Huxley writes:

One of the reasons for the lack of attention to the training of the mind-body is that this particular kind of teaching does not fall into any academic pigeonhole. This is one of the great problems in education: Everything takes place in a pigeonhole… The pigeonholes must be there because we cannot avoid specialization; but what we do need in academic institutions now is a few people who run about on the woodwork between the pigeonholes, and peep into all of them and see what can be done, and who are not closed to disciplines which do not happen to fit into any of the categories considered as valid by the present educational system!

The solution to this paralyzing rigidity, Huxley argues, lies in combining “relaxation and activity.” In a sentiment that calls to mind the Chinese concept of wu-wei —“trying not to try” — he writes:

Take the piano teacher, for example. He always says, Relax, relax. But how can you relax while your fingers are rushing over the keys? Yet they have to relax. The singing teacher and the golf pro say exactly the same thing. And in the realm of spiritual exercises we find that the person who teaches mental prayer does too. We have somehow to combine relaxation with activity…The personal conscious self being a kind of small island in the midst of an enormous area of consciousness — what has to be relaxed is the personal self, the self that tries too hard, that thinks it knows what is what, that uses language. This has to be relaxed in order that the multiple powers at work within the deeper and wider self may come through and function as they should. In all psychophysical skills we have this curious fact of the law of reversed effort: the harder we try, the worse we do the thing.

Two decades before Julia Cameron penned her enduring psychoemotional toolkit for getting out of your own way, Huxley makes a beautiful case for the same idea:

We have to learn, so to speak, to get out of our own light, because with our personal self — this idolatrously worshiped self — we are continually standing in the light of this wider self — this not-self, if you like — which is associated with us and which this standing in the light prevents. We eclipse the illumination from within. And in all the activities of life, from the simplest physical activities to the highest intellectual and spiritual activities, our whole effort must be to get out of our own light.

The seed for this lifelong effort, Huxley concludes, must be planted in early education:

These [are] extremely important facets of education, which have been wholly neglected. I do not think that in ordinary schools you could teach what are called spiritual exercises, but you could certainly teach children how to use themselves in this relaxedly active way, how to perform these psychophysical skills without the frightful burden of overcoming the law of reversed effort.

The Divine Within is an illuminating read in its totality, exploring such subjects as time, religion, distraction, death, and the nature of reality. Complement it with Alan Watts on learning to live with presence in the age of anxiety and the great Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh on how to love.

Oda a la tristeza - Poemas de Pablo Neruda

Tristeza, escarabajo

de siete patas rotas,

huevo de telaraña,

rata descalabrada,

esqueleto de perra:

Aquí no entras.

No pasa.

Ándate.

Vuelve

al sur con tu paraguas,

vuelve

al norte con tus dientes de culebra.

Aquí vive un poeta.

La tristeza no puede

entrar por estas puertas.

Por las ventanas

entra el aire del mundo,

las rojas rosas nuevas,

las banderas bordadas

del pueblo y sus victoria.

No puedes.

Aquí no entras.

Sacude

tus alas de murciélago,

yo pisaré las plumas

que caen de tu mano,

yo barreré los trozos

de tu cadáver hacia

las cuatro puntas del viento,

yo te torceré el cuello,

te coseré los ojos,

cortaré tu mortaja

y enterraré, tristeza, tus huesos roedores

bajo la primavera de un manzano.

Cuando yo muera quiero tus manos en mis ojos:

quiero la luz y el trigo de tus manos amadas

pasar una vez más sobre mí su frescura:

sentir la suavidad que cambió mi destino.

Quiero que vivas mientras yo, dormido, te espero,

quiero que tus oídos sigan oyendo el viento,

que huelas el aroma del mar que amamos juntos

y que sigas pisando la arena que pisamos.

Quiero que lo que amo siga vivo

y a ti te amé y canté sobre todas las cosas,

por eso sigue tú floreciendo, florida,

para que alcances todo lo que mi amor te ordena,

para que se pasee mi sombra por tu pelo,

para que así conozcan la razón de mi canto.

Lee todo en: http://www.poemas-del-alma.com/pablo-neruda-oda-a-la-tristeza.htm#ixzz3zGhUZTf8

de siete patas rotas,

huevo de telaraña,

rata descalabrada,

esqueleto de perra:

Aquí no entras.

No pasa.

Ándate.

Vuelve

al sur con tu paraguas,

vuelve

al norte con tus dientes de culebra.

Aquí vive un poeta.

La tristeza no puede

entrar por estas puertas.

Por las ventanas

entra el aire del mundo,

las rojas rosas nuevas,

las banderas bordadas

del pueblo y sus victoria.

No puedes.

Aquí no entras.

Sacude

tus alas de murciélago,

yo pisaré las plumas

que caen de tu mano,

yo barreré los trozos

de tu cadáver hacia

las cuatro puntas del viento,

yo te torceré el cuello,

te coseré los ojos,

cortaré tu mortaja

y enterraré, tristeza, tus huesos roedores

bajo la primavera de un manzano.

Cuando yo muera quiero tus manos en mis ojos:

quiero la luz y el trigo de tus manos amadas

pasar una vez más sobre mí su frescura:

sentir la suavidad que cambió mi destino.

Quiero que vivas mientras yo, dormido, te espero,

quiero que tus oídos sigan oyendo el viento,

que huelas el aroma del mar que amamos juntos

y que sigas pisando la arena que pisamos.

Quiero que lo que amo siga vivo

y a ti te amé y canté sobre todas las cosas,

por eso sigue tú floreciendo, florida,

para que alcances todo lo que mi amor te ordena,

para que se pasee mi sombra por tu pelo,

para que así conozcan la razón de mi canto.

Lee todo en: http://www.poemas-del-alma.com/pablo-neruda-oda-a-la-tristeza.htm#ixzz3zGhUZTf8

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)